Reproducibility II: Run Containers¶

Learning Objectives

After this lesson, you should be able to:

- Explain what containers are used for in reproducible research contexts

- Search for and run a Docker container locally or on a remote system

- Understand how version control and data can be used inside a container

Reproducible Computer Code¶

Sharing your scientific analysis code with your colleagues is an essential pillar of Open Science that will help push your field forward.

There are, however, technical challenges that may prevent your colleagues from effectively running your code on their computers. In the previous lesson Reproducibility I we described computing environments and how they can make it difficult to run code from one computer to another.

Solutions for Sharing Computer Code¶

-

Create a custom environment and share the recipe so your colleauges can replicate on their computer (as shown in Reproducibility I)

-

Package up the code and all of the software and send it to your colleague as a Container

What are containers?¶

A container is a standard unit of software that packages up code and all its dependencies so the application runs quickly and reliably from one computing environment to another

- Container images are a lightweight, standalone, executable package of software that includes everything needed to run an application: code, runtime, system tools, system libraries and settings

- Each of these elements are specifically versioned and do not change

- The recipient does not need to install the software in the traditional sense

A useful analogy is to think of software containers as shipping containers. It allows us move cargo (software) around the world in standard way. The shipping container can be offloading and executed anywhere, as long the destination has a shipping port (i.e., Docker)

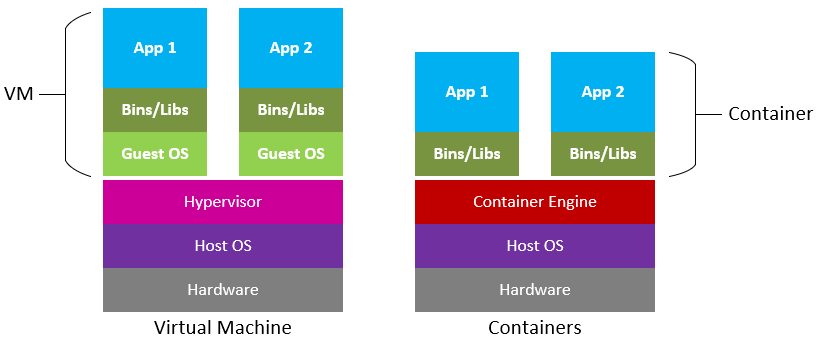

Containers are similar to virtual machines (VMs), but are smaller and easier to share. A big distinction between Containers and VMs is what is within each environment: VMs require the OS to be present within the image, whilst containers rely on the host OS and the container engine (e.g., Docker Engine).

Containers for Reproducible Science¶

Software containers, such as those managed by Docker or Singularity, are incredibly useful for reproducible science for several reasons:

Environment Consistency:¶

Containers encapsulate the software environment, ensuring that the same versions of software, libraries, and dependencies are used every time, reducing the "it works on my machine" problem.

- Ease of Sharing:

- Containers can be easily shared with other researchers, allowing them to replicate the exact software environment used in a study.

- Platform Independence:

- Containers can run on different operating systems and cloud platforms, allowing for consistency across different hardware and infrastructure.

- Version Control:

- Containers can be versioned, making it easy to keep track of changes in the software environment over time.

- Scalability:

- Containers can be easily scaled and deployed on cloud infrastructure, allowing for reproducible science at scale.

- Isolation:

- Containers isolate the software environment from the host system, reducing the risk of conflicts with other software and ensuring a clean and controlled environment.

The most common container software is Docker, which is a platform for developers and sysadmins to develop, deploy, and run applications with containers. Apptainer (formerly, Singularity), is another popular container engine, which allows you to deploy containers on HPC clusters.

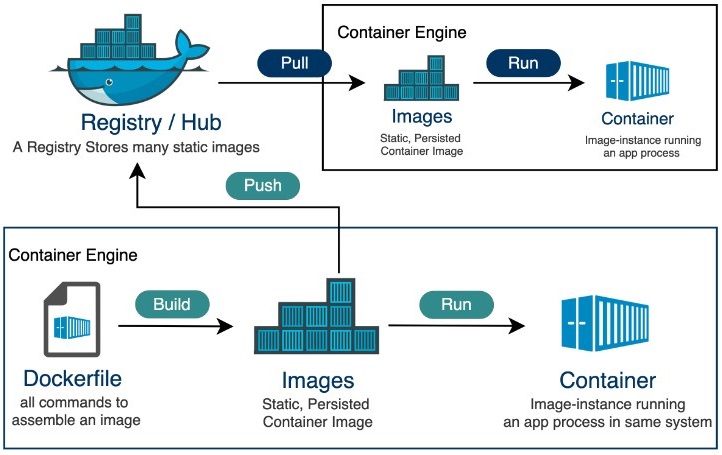

DockerHub is the world's largest respository of container images. Think of it as the 'Github' of container images. It facilitates collaboration amongst developers and allows you to share your container images with the world. Dockerhub allows users to maintain different versions of container images.

While Docker allows you to quickly run software from other people, it may not work across every platform.

There are different CPU architectures (arm, amd64, x64, x86) deployed across cloud, computer workstations, laptops, and cellular phones. Docker containers and their software can be cross-compiled across architectures, but this must be done by the creators.

Introduction to Docker¶

Prerequisites¶

In order to complete these exercises we STRONGLY recommend that you set up a personal GitHub and DockerHub account (account creation for both services is free).

There are no specific skills needed for this tutorial beyond elementary command line ability and using a text editor.

We are going to be using GitHub CodeSpaces for the hands on portion of the workshop, which features VS Code as a fully enabled development environment with Docker already installed.

Our instructions on starting a new CodeSpace are here.

Installing Docker on your personal computer

We are going to be using virtual machines on the cloud for this course, and we will explain why this is a good thing, but there may be a time when you want to run Docker on your own computer.

Installing Docker takes a little time but it is reasonably straight forward and it is a one-time setup.

Installation instructions from Docker Official Docs for common OS and chip architectures:

Never used a terminal before?

Before venturing much further, you should review the Software Carpentry lessons on "The Unix Shell" and "Version Control with Git" -- these are great introductory lessons related to the skills we're teaching here.

You've given up on ever using a terminal? No problem, Docker can be used from graphic interfaces, like Docker Desktop, or platforms like Portainer. We suggest you read through their documentation on how to use Docker.

Fundamental Docker Commands ¶

Docker commands in the terminal use the prefix docker.

For every command listed, the correct execution of the commands through the command line is by using docker in front of the command: for example docker help or docker search. Thus, every = docker.

help¶

Like many other command line applications the most helpful flag is the help command which can be used with the Management Commands:

$ docker

$ docker --help

search¶

We talk about the concept of Docker Registries in the next section, but you can search the public list of registeries by using the docker search command to find public containers on the Official Docker Hub Registry:

$ docker search

pull¶

Go to the Docker Hub and type hello-world in the search bar at the top of the page.

Click on the 'tag' tab to see all the available 'hello-world' images.

Click the 'copy' icon at the right to copy the docker pull command, or type it into your terminal:

$ docker pull hello-world

Note

If you leave off the : and the tag name, it will by default pull the latest image

$ docker pull hello-world

Using default tag: latest

latest: Pulling from library/hello-world

2db29710123e: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:bfea6278a0a267fad2634554f4f0c6f31981eea41c553fdf5a83e95a41d40c38

Status: Downloaded newer image for hello-world:latest

docker.io/library/hello-world:latest

Now try to list the files in your current working directory:

$ ls -l

Where is the image you just pulled?

Docker saves container images to the Docker directory (where Docker is installed).

You won't ever see them in your working directory.

Use 'docker images' to see all the images on your computer:

$ docker images

run¶

The single most common command that you'll use with Docker is docker run (see official help manual for more details).

$ docker run hello-world:latest

In the demo above, you used the docker pull command to download the hello-world:latest image.

What about if you run a container that you haven't downloaded?

$ docker run alpine:latest

When you executed the command docker run alpine:latest, Docker first looked for the cached image locally, but did not find it, it then ran a docker pull behind the scenes to download the alpine:latest image and then execute your command.

images¶

You can now use the docker images command to see a list of all the cached images on your system:

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED VIRTUAL SIZE

alpine latest c51f86c28340 4 weeks ago 1.109 MB

hello-world latest 690ed74de00f 5 months ago 960 B

Inspecting your containers

To find out more about a Docker images, run docker inspect hello-world:latest

ps¶

Now it's time to see the docker ps command which shows you all containers that are currently running on your machine.

docker ps

Since no containers are running, you see a blank line.

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

Let's try a more useful variant: docker ps --all

$ docker ps --all

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

a5eab9243a15 hello-world "/hello" 5 seconds ago Exited (0) 3 seconds ago loving_mcnulty

3bb4e26d2e0c alpine:latest "/bin/sh" 17 seconds ago Exited (0) 16 seconds ago objective_meninsky

192ffdf0cbae opensearchproject/opensearch-dashboards:latest "./opensearch-dashbo…" 3 days ago Exited (0) 3 days ago opensearch-dashboards

a10d47d3b6de opensearchproject/opensearch:latest "./opensearch-docker…" 3 days ago Exited (0) 3 days ago opensearch-node1

What you see above is a list of all containers that you have run.

Notice that the STATUS column shows the current condition of the container: running, or as shown in the example, when the container was exited.

stop¶

The stop command is used for containers that are actively running, either as a foreground process or as a detached background one.

You can find a running container using the docker ps command.

rm¶

You can remove individual stopped containers by using the rm command. Use the ps command to see all your stopped contiainers:

@user ➜ /workspaces $ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

03542eaac9dc hello-world "/hello" About a minute ago Exited (0) About a minute ago unruffled_nobel

Use the first few unique alphanumerics in the CONTAINER ID to remove the stopped container:

@user ➜ /workspaces (mkdocs ✗) $ docker rm 0354

0354

Check to see that the container is gone using ps -a a second time (-a is shorthand for --all; the full command is docker ps -a or docker ps --all).

rmi¶

The rmi command is similar to rm but it will remove the cached images. Used in combination with docker images or docker system df you can clean up a full cache

docker rmi

@user ➜ /workspaces/ (mkdocs ✗) $ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

opendronemap/webodm_webapp latest e075d13aaf35 21 hours ago 1.62GB

redis latest a10f849e1540 5 days ago 117MB

opendronemap/nodeodm latest b4c50165f838 6 days ago 1.77GB

hello-world latest feb5d9fea6a5 7 months ago 13.3kB

opendronemap/webodm_db latest e40c0f274bba 8 months ago 695MB

@user ➜ /workspaces (mkdocs ✗) $ docker rmi hello-world

Untagged: hello-world:latest

Untagged: hello-world@sha256:10d7d58d5ebd2a652f4d93fdd86da8f265f5318c6a73cc5b6a9798ff6d2b2e67

Deleted: sha256:feb5d9fea6a5e9606aa995e879d862b825965ba48de054caab5ef356dc6b3412

Deleted: sha256:e07ee1baac5fae6a26f30cabfe54a36d3402f96afda318fe0a96cec4ca393359

@user ➜ /workspaces (mkdocs ✗) $

system¶

The system command can be used to view information about containers on your cache, you can view your total disk usage, view events or info.

You can also use it to prune unused data and image layers.

To remove all cached layers, images, and data you can use the -af flag for all and force

docker system prune -af

tag¶

By default an image will recieve the tag latest when it is not specified during the docker build

Image names and tags can be created or changed using the docker tag command.

docker tag imagename:oldtag imagename:newtag

You can also change the registry name used in the tag:

docker tag docker.io/username/imagename:oldtag harbor.cyverse.org/project/imagename:newtag

The cached image laters will not change their sha256 and both image tags will still be present after the new tag name is generated.

Example of Running a Container¶

This is a tutorial to demonstrate how to run PDAL using Docker. PDAL is a stand-alone software package that can analyze and manipulate point cloud data files such as .las and .laz. In this tutorial, we will convert a LiDAR .laz file into a Cloud-optimized Point Cloud format (.copc.laz).

1. Clone this repository to your local machine

git clone https://github.com/jeffgillan/pdal_copc.git

2. Change directories into the newly cloned repository

cd pdal_copc

3. Run the Container

docker run -v $(pwd):/data jeffgillan/pdal_copc:1.0

You are mounting a local volume (-v) directory to the container (/data). This local directory should have all of the point clouds files you want to convert. $(pwd) is telling it that the point clouds are in the current working directory.

jeffgillan/pdal_copc:1.0 is the name of the container image you want to run.

jeffgillan = the Dockerhub account name

pdal_copc = the name of the image

1.0 = the tag name

Your if everything worked correctly, you should have a new file tree.copc.laz in your present working directory.

Working with Interactive Containers¶

Let's go ahead and run some Integrated Development Environment images from "trusted" organizations on the Docker Hub Registry.

Jupyter Lab¶

In this section, let's find a Docker image which can run a Jupyter Notebook

Search for official images on Docker Hub which contain the string 'jupyter'

$ docker search jupyter

It should return something like:

NAME DESCRIPTION STARS OFFICIAL AUTOMATED

jupyter/datascience-notebook Jupyter Notebook Data Science Stack from htt… 912

jupyter/all-spark-notebook Jupyter Notebook Python, Scala, R, Spark, Me… 374

jupyter/scipy-notebook Jupyter Notebook Scientific Python Stack fro… 337

jupyterhub/jupyterhub JupyterHub: multi-user Jupyter notebook serv… 307 [OK]

jupyter/tensorflow-notebook Jupyter Notebook Scientific Python Stack w/ … 298

jupyter/pyspark-notebook Jupyter Notebook Python, Spark, Mesos Stack … 224

jupyter/base-notebook Small base image for Jupyter Notebook stacks… 168

jupyter/minimal-notebook Minimal Jupyter Notebook Stack from https://… 150

jupyter/r-notebook Jupyter Notebook R Stack from https://github… 44

jupyterhub/singleuser single-user docker images for use with Jupyt… 43 [OK]

jupyter/nbviewer Jupyter Notebook Viewer 27 [OK]

Untrusted community images

An important thing to note: None of these Jupyter or RStudio images are 'official' Docker images, meaning they could be trojans for spyware, malware, or other nasty warez.

Understanding PORTS¶

When we want to run a container that runs on the open internet, we need to add a TCP or UDP port number from which we can access the application in a browser using the machine's IP (Internet Protocol) address or DNS (Domain Name Service) location.

To do this, we need to access the container over a separate port address on the machine we're working on.

Docker uses the flag --port or -p for short followed by two sets of port numbers.

Exposing Ports

Docker can in fact expose all ports to a container using the capital -P flag

For security purposes, it is generally NEVER a good idea to expose all ports.

Typically these numbers can be the same, but in some cases your machine may already be running another program (or container) on that open port.

The port has two sides left:right separated by a colon. The left side port number is the INTERNAL port that the container software thinks its using. The right side number is the EXTERNAL port that you can access on your computer (or virtual machine).

Here are some examples to run basic RStudio and Jupyter Lab:

$ docker run --rm -p 8787:8787 -e PASSWORD=cc2022 rocker/rstudio

note: on CodeSpaces, the reverse proxy for the DNS requires you to turn off authentication

$ docker run --rm -p 8787:8787 -e DISABLE_AUTH=true rocker/rstudio

$ docker run --rm -p 8888:8888 jupyter/base-notebook

docker run --rm -p 8888:8888 jupyter/base-notebook start-notebook.sh --NotebookApp.token='' --NotebookApp.password=''

Preempting stale containers from your cache

We've added the --rm flag, which means the container will automatically removed from the cache when the container is exited.

When you start an IDE in a terminal, the terminal connection must stay active to keep the container alive.

Detaching your container while it is running¶

If we want to keep our window in the foreground we can use the -d - the detached flag will run the container as a background process, rather than in the foreground.

When you run a container with this flag, it will start, run, telling you the container ID:

$ docker run --rm -d -p 8888:8888 jupyter/base-notebook

To view the running container, use the docker ps command.

Interactive Commands with Containers¶

Lets try another command, this time to access the container as a shell:

$ docker run alpine:latest sh

Wait, nothing happened, right?

Is that a bug?

Well, no.

The container will exit after running any scripted commands such as sh, unless they are run in an "interactive" terminal (TTY) - so for this example to not exit, you need to add the -i for interactive and -t for TTY. You can run them both in a single flag as -it, which is the more common way of adding the flag:

$ docker run -it alpine:latest sh

The prompt should change to something more like / #.

You are now running a shell inside the container!

Try out a few commands like ls -l, uname -a and others.

Exit out of the container by giving the exit command.

/ # exit

Making sure you've exited the container

If you type exit your container will exit and is no longer active. To check that, try the following:

$ docker ps --latest

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

de4bbc3eeaec alpine "/bin/sh" 3 minutes ago Exited (0) About a minute ago pensive_leavitt

If you want to keep the container active, then you can use keys ctrl +p ctrl +q. To make sure that it is not exited run the same docker ps --latest command again:

$ docker ps --latest

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

0db38ea51a48 alpine "sh" 3 minutes ago Up 3 minutes elastic_lewin

Now if you want to get back into that container, then you can type docker attach <container id>. This way you can save your container:

$ docker attach 0db38ea51a48

House Keeping and Cleaning Up Exited Containers¶

Managing Docker Images¶

In the previous example, you pulled the alpine image from the registry and asked the Docker client to run a container based on that image. To see the list of images that are available locally on your system, run the docker images command.

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

ubuntu bionic 47b19964fb50 4 weeks ago 88.1MB

alpine latest caf27325b298 4 weeks ago 5.53MB

hello-world latest fce289e99eb9 2 months ago 1.84kB

Above is a list of images that I've pulled from the registry. You will have a different list of images on your machine. The TAG refers to a particular snapshot of the image and the ID is the corresponding unique identifier for that image.

For simplicity, you can think of an image akin to a Git repository - images can be committed with changes and have multiple versions. When you do not provide a specific version number, the client defaults to latest.

Clutter and Cache¶

Docker images are cached on your machine in the location where Docker was installed. These image files are not visible in the same directory where you might have used docker pull <imagename>.

Some Docker images can be large. Especially data science images with many scientific programming libraries and packages pre-installed.

Pulling many images from the Docker Registries may fill up your hard disk! To inspect your system and disk use:

$ docker system info

$ docker system df

To find out how many images are on your machine, type:

$ docker images

To remove images that you no longer need, type:

$ docker system prune

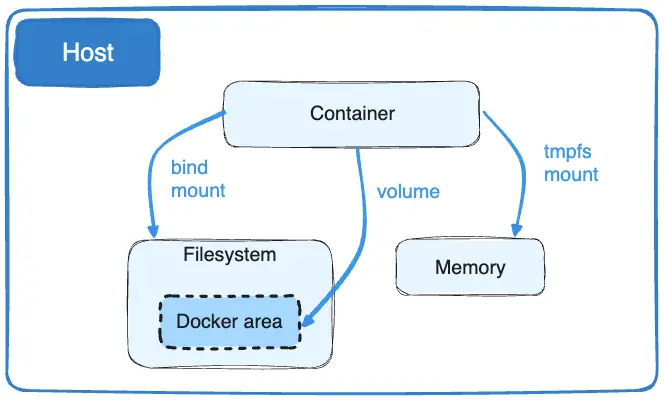

This is where it becomes important to differentiate between images, containers, and volumes (which we'll get to more in a bit). You can take care of all of the dangling images and containers on your system.

Note, that prune will not remove your cached images

$ docker system prune

WARNING! This will remove:

- all stopped containers

- all networks not used by at least one container

- all dangling images

- all dangling build cache

Are you sure you want to continue? [y/N]

If you added the -af flag it will remove "all" -a dangling images, empty containers, AND ALL CACHED IMAGES with "force" -f.

Managing Data in Docker¶

It is possible to store data within the writable layer of a container, but there are some limitations:

- The data doesn’t persist when that container is no longer running, and it can be difficult to get the data out of the container if another process needs it.

- A container’s writable layer is tightly coupled to the host machine where the container is running. You can’t easily move the data somewhere else.

- Its better to put your data into the container AFTER it is built - this keeps the container size smaller and easier to move across networks.

Docker offers three different ways to mount data into a container from the Docker host: Volumes, tmpfs mounts and bind mounts. Here, we will only be exploring Volumes.

Why Volumes?

Volumes are often a better choice than persisting data in a container’s writable layer, because using a volume does not increase the size of containers using it, and the volume’s contents exist outside the lifecycle of a given container. Some of the advantages of volumes include:

- Volumes are easier to back up or migrate.

- You can manage volumes using Docker CLI commands or the Docker API.

- Volumes work on both UNIX and Windows containers.

- Volumes can be more safely shared among multiple containers.

- A new volume’s contents can be pre-populated by a container.

The -v flag is used for mounting volumes:

-v or --volume: Consists of three fields, separated by colon characters (:).

The fields must be in the correct order, and the meaning of each field is not immediately obvious.

Required:

- The first field is the path on your local machine that where the data are.

- The second field is the path where the file or directory are mounted in the container.

Optional:

- The third field is optional, and is a comma-separated list of options, such as

ro(read only).

The synthax looks like the following:

-v /home/username/your_data_folder:/container_folder

This is what a full docker command with a mounted volume looks like:

$ docker run -v /home/$USER/read_cleanup:/work alpine:latest ls -l /work

So what if we wanted to work interactively inside the container?

$ docker run -it -v /home/$USER/read_cleanup:/work alpine:latest sh

Once you're in the container, you will see that the /work directory is mounted in the working directory.

Any data that you add to that folder outside the container will appear INSIDE the container. And any work you do inside the container saved in that folder will be saved OUTSIDE the container as well.

Docker Commands¶

Here is a compiled list of fundamental Docker Commands:

| Command | Usage | Example |

|---|---|---|

pull |

Downloads an image from Docker Hub | docker pull hello-world:latest |

run |

runs a container with entrypoint | docker run -it user/image:tag |

build |

Builds a docker image from a Dockerfile in current working directory | docker build -t user/image:tag . |

images |

List all images on the local machine | docker images list |

tag |

Adds a different tag name to an image | docker tag hello-world:latest hello-world:new-tag-name |

login |

Authenticate to the Docker Hub (requires username and password) | docker login |

push |

Upload your new image to the Docker Hub | docker push user/image:tag |

inspect |

Provide detailed information on constructs controlled by Docker | docker inspect containerID |

ps |

List all containers on your system | docker ps -a |

rm |

Delete a stopped or running container | docker rm -f <container ID> |

rmi |

Delete an image from your cache | docker rmi hello-world:latest |

stop |

Stop a running container | docker stop alpine:latest |

system |

View system details, remove old images and containers with prune |

docker system prune |

push |

Uploads an image to the Docker Hub (or other private registry) | docker push username/image:tag |

Self Assessment¶

A Docker container with the tagname latest ensures old code and data will work on a new computer setup?

Answer

Never use the latest tag for a publication or archival.

The latest version is always being updated and should be considered "cutting edge".

latest is the default tag name of all Docker images

latest versions MAY have backward compatibility with older code and data, but this is not always a given

When are containers the right solution?

Success

Containers are valuable when you need to run an analyses on a remote platform, and you need it to work every time.

Failure

You need to do some simple text file editing

You need to run a web service

True or False: Docker containers allow for reproducibility across all computing platforms

False

While Docker allows you to quickly run software from other people, it may not work across every platform.

There are different CPU architectures (arm, amd64, x64, x86) deployed across cloud, computer workstations, laptops, and cellular phones.

Docker containers and their software can be cross-compiled across architectures, but this must be done by the creators.

When is it advisable to not trust a Docker image?

When you cannot view its Dockerfile

Featured and Verified Docker images can be trusted, in general.

User generated images should not be trusted unless you can view their Dockerfile, or build logs to determine what is actually in the container you are attempting to run.

Additional Resources¶

Deeper Exploration of Containers and how to create them can be found here

The Carpentries have an incubator workshop on Docker Containers